Wednesday's Words of Quality,

Lesson #12: Daily Management

Richard Zarbo, MD © 2022 Wednesday’s Words of Quality

Lesson #12 of 13

The managerial discipline of Daily Management (DM) has become a major subsystem supporting our business effectiveness by promoting visual workflow management, local accountability and daily problem solving within work units. DM now provides structure for all local area leaders to facilitate numerous, small team-based continuous improvements through daily tactical monitoring of a balanced set of critical metrics focused on internal and external customers. In effect, DM defines leader standard work and changes the paradigm for managing. DM is not a mere checklist for managers but rather the business system by which managers with their team members connect the local processes under their control to the higher-level business strategic objectives by monitoring and targeting failing processes for improvement within a 24-hour measurement cycle.

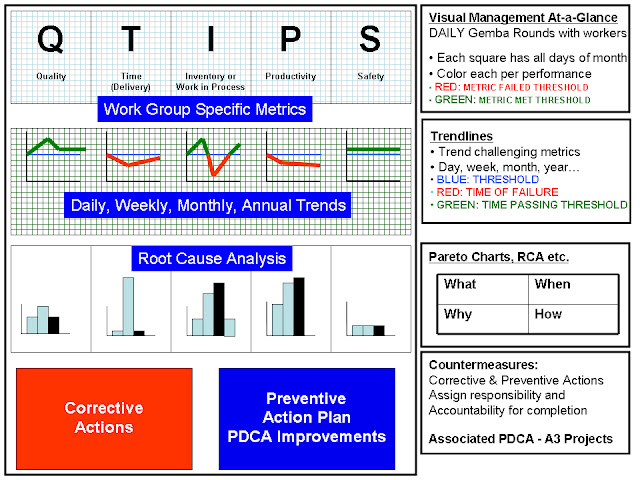

We learned our approach to Daily Management (DM) from the business systems of Toyota and Danaher Corporations and customized our daily managed metrics under the acronym QTIPS- Quality, Time, Inventory, Productivity and Safety. In this lesson, we present our standardized approach to DM and share examples of successful local problem solving within and across laboratory units at the level of the work and extending beyond the laboratory’s walls to clinical suppliers and customers. (1)

The simplest definition of DM was offered by Liker as “the process of checking actual versus target results and engaging the team in creative problem solving.” But his reflection that “The goal is as much to develop people as to get the results.” is key in understanding how DM reinforces the cultural expectation of continuous improvement at the ground level of any organization. (2) The concept and practice of DM may, therefore, be viewed differently based on maturity levels of Lean adoption so we will frame this discussion along several lines as DM is a management subsystem for leaders, managers and the workforce to promote engagement and continuous improvements aligned with corporate goals.

DM Methodology and Elements

Board Layout for Problem Solving- Rows

The layout for each measure is standardized into five rows that promoted visual data display for ready assessment, trending, root cause analysis, corrective and preventive actions as illustrated below.

Row 1 is the display of a calendar month superimposed on one of the QTIPS letters with a circle for each day to be marked as a green day (i.e, passed performance) or red day (i.e. failed performance) based on the previous 24 hour performance. No yellow is used. If the laboratory did not operate on a specific day, the circle is colored black. This sheet is unmarked at the beginning of the month and is progressively filled out over the month with daily performance (red, green or black). Additionally, the Row 1 sheet also lists information defining the metric and the standard, the owner of that metric and the time of Gemba review.

Row 2 is the actual the performance of the metric during the previous 24-hour period. This is commonly either a LIS-generated report or a manually plotted form that provides information reflecting the performance deviation from standard.

Row 3 is a graph of the measure’s performance trended over an extended period of time (weeks to the calendar year). This trend is based on information captured from Row 1.

Row 4 is composed of 2 Pareto charts. The left side is for a generic first-pass Pareto analysis (when and what) capturing the nature/root-cause for all failure days. The right side is a focused Pareto analysis (where and how) reflecting a deeper dive characterization of a specific root-cause on the left side that is being actively pursued.

Row 5 is divided into 2 tables. The first table is a Corrective Action Table that captures the details of immediate interventions taken to correct performance failures, anticipated completion date of the intervention, current status of the intervention and responsible personnel. The second table is a Preventive Action Table that identifies similar information for derived PDCA-based projects being tested to eliminate root causes.

Rows 1-5 are printed on separate A4 paper sheets and mounted in a linear fashion at individual workstations. Depending on available space, these DM boards take the form of wall mountings with plastic inserts to hold the paper forms or mobile rotating columns with plastic inserts fastened by magnets.

DM as a Subsystem of a Mature Lean Enterprise

After a decade of practical experience in adapting Lean management to laboratories and other clinical domains in healthcare, we have come to appreciate that Lean is first a management system that structures and incentivizes leaders, managers, and the workforce to align their efforts to continually improve the work systems, services and products for which they are each responsible. We have further come to know that success requires creating effective and aligned new management subsystems that support the philosophy and work of a continuous improvement culture. The main business subsystems that enable this culture of continuous improvement to function at all levels are policy deployment at the leadership level, DM at the managerial level, nonconformance (deviation) management at the level of the work and the PDCA based continuous improvement system at all levels. DM is the subsystem responsible for aligning people to cultivate a culture of problem solving at the level of the work.

Prerequisites for Effective DM and Continuous Improvement

For Lean to be successful as the basis of continuous improvement, leaders must create and then support grass roots improvements. This requires that the ground has already been prepared, the grass has been fertilized and the root system will be continually watered and fed.

Success in using a DM approach to continuous improvement with workforce engagement is predicated on the foundation of a preexisting and functional subsystem structure of work groups with respective group leaders (manager), team leaders for quality improvement and work team members. Liker describes this structure at Toyota, and we have described this structure previously for laboratories. (2,3) The other prerequisites are a trained workforce who understands the goals and rules of continuous improvement and the establishment of a blame-free culture that enables work defects to be consistently identified and analyzed as the basis for daily improvement at the level of the work site. The last element is a dedicated and aligned manager without whom the DM process may die on the vine.

The Function of DM

The DM subsystem visually holds managers and teams responsible for executing their piece of the strategic plan at the local level by providing structure and discipline for managers and work teams to link work group performance to departmental metrics and organizational objectives. The business systems of advanced and successful Lean corporations like Toyota and Danaher rely on DM to make visible each team’s contribution, success or failure in achieving corporate goals so that adjustments and countermeasure solutions derived from sound problem solving can be addressed sooner and in a locally meaningful way.

One of the most important structures for continuous improvement from the base of the organization is a daily visual management system. For example, the Toyota Floor Management Development System focuses the current performance of the work group relative to expected targets organized by major key performance indicator categories of Safety, Quality, Productivity (delivery, service), Cost and People (human resource development, engagement). (2) The DM boards of Danaher Corporation’s business entities revolve around Safety, Quality, Delivery, Inventory, and Productivity. Through our interaction with Danaher, we evolved the DM system of the Henry Ford Production System laboratories to focus process improvements in the categories of Quality, Time (delivery), Inventory (work in-process, batch size, instrument availability), Productivity and Safety. These DM measures are represented by the acronym QTIPS.

What DM Is

DM is a powerful visual management subsystem that provides managers and teams with local structure, alignment, focus and accountability for continuous improvements of their group’s product or service. When structured by sequential workstations along the path of workflow, DM serves to make visible defective work design resulting in substandard quality. In this fashion, DM also serves to break down barriers of control and isolation that preclude the achievement of continuous flow that is so vital to Lean success. This is illustrated in the surgical pathology laboratory example of inventory monitoring. Here group examination for root cause determined that specimen batches left over between shifts resulted not from excess work but because practices adopted unknowingly upstream greatly magnified downstream work and batch accumulation.

What DM is Not

DM is not a display of stable production or operational efficiency numbers or a posting of weekly collected data measures. DM is a daily problem-solving tool for managers and teams to identify daily countermeasures and opportunities to eliminate work problems that miss local area targets through data driven problem solving. Therefore philosophically, DM measures should not be fixed but should change as teams identify opportunities, understand root causes, improve and bring the situation under control to stability. The visual trend of “red” days transitioning to “green” is the simplistic signal to all that strategically aligned goals have been achieved in a stable work system.

DM in Advanced Lean Transformation

We believe that DM is a higher order systematized Lean activity that requires the cultural attributes of managerial ownership and blame-free, team-based accountability for continuous improvement in a work system that has already achieved reasonably standardized and stable process flow. Many are enamored of the highly visible results of DM but it would be a mistake to require the discipline of DM in a chaotic system of work, as this would surely court frustration and failure. Stability can be managed by DM, perpetual crisis cannot.

Liker has described the natural progression of Lean business transformation in 3 phases as Lean evolves from consultant lead application of tools in kaizen events to middle management ownership with Lean thinking and problem solving to enterprise-wide engagement with local ownership of Lean by leaders and all employees. The mature result is an aligned culture of continuous process improvement. Notably, Lean does not progress beyond consultant lead efforts until middle level managers buy into the culture change and model new behaviors that result in problem solving with their staff. This is why DM is such an effective management approach for the conversion and continued education of middle level managers in securing Lean from top to bottom in the organization. (4)

DM Standardizes How Managers Manage

Of the main subsystems that drive quality from top to bottom in a Lean enterprise, DM is targeted to managers who are directly responsible for work outcomes. In effect, DM, if properly structured, defines the “standard work” of the manager and assists them in succeeding not only as leaders but in achieving corporate and departmental goals that are cascaded to them. The manager’s role in Lean is to understand the reliability and consistency of their work product or service and to know the variability or lack of control in their processes and then how to right that condition.

DM provides managers with structure for tightly managing areas within their control by assessing performance compared to benchmark goals within a 24-hour framework. Close examination of critical elements of performance allows for better analysis of root cause, implementation of immediate countermeasures to correct the deficit, shared accountability with the workforce and development of team-based PDCA process improvements as corrective and preventive actions whose impact can be assessed and sustained.

We had previously attempted to assist our managers’ abilities to manage by creating managers’ weekly checklists or a manager’s standard work. These were helpful in creating an expectation of uniform discipline but as with any checklist, it can be ignored, periodically skipped, or truncated. This required the use of audits to assure compliance. The flaw in a checklist is that it is not visible and that it requires rework in the form of an audit until the behavior becomes rote.

Although each of our laboratory operations had been using regular metrics of performance, those metrics varied in quality of measure related to criticality of operational success, frequency of monitoring and corrective action taken, if any, and assessment of effectiveness. Therefore, we approached the use of DM with some trepidation understanding fully the requisite role of managers to buy into the process for success. That the managers at our main campus core laboratories readily adopted DM after only 1 and ½ days of training, can be attributed to the stability of our Lean culture, then in its 8th year of maturity, the constant push to seek of opportunities for improvement and the functionality of the DM system to effect meaningful change.

We have found that DM is a superior system of management in that it provides a daily visible update of an area’s progress toward goals and objectives to all who pass by the board. The state of affairs of a work area is apparent at a glance as to whether the problem is an opportunity for improvement being addressed by a countermeasure and the current stage of problem ownership and resolution. We have designed our DM system to incorporate documentation of corrective/preventive actions and PDCA problem solving to assist managers in engaging and developing their employees in Lean thinking and ownership of local problems within the day.

DM and Continuous Improvement (Kaizen)

The vital role of DM in continuous improvement is best grasped by understanding the culture of Toyota. According to Liker, “Toyota believes that improvement cannot be continuous if it is left to a small number of process improvement experts working for senior management. Continuous improvement is possible only if team members across the organization are continually checking their progress relative to goals and taking corrective actions to address problems. Continuous improvement starts at the work group level, where value-added work is done. At Toyota, that is at the level of work teams, where group leaders and team leaders facilitate daily kaizen”. (2)

According to Liker, kaizen is often misunderstood as a special project team using technical approaches to improvement (lean or six sigma) to address a problem or a weeklong kaizen event staffed with select members to “make a burst of changes”. (2)

Kaizen, according to Liker, consists of 2 types that require daily activity- maintenance kaizen and improvement kaizen. (2) Our approach to DM and the boards we have created support both types of daily improvement activities at the level of the work.

Maintenance kaizen is the initial assessment of success or failure in daily adaptations or reactions to unpredictable work variations. These are the metrics of daily work stability of performance that we have categorized on our DM Boards as quality, timeliness, inventory, productivity, and safety. Immediate and urgent countermeasures (corrective actions) taken to bring the work system back to stability are documented on the board and then followed by a root cause analysis with the intent of preventing recurrence (preventive actions).

We have integrated into our DM Boards the second type of kaizen, the improvement, based on PDCA problem resolution that is intent on preventing the work problem from occurring or testing innovations raising the performance bar. In truth, the improvement kaizen is rarely a daily accomplishment, but the presence of this category on the board maintains the team focus on the ultimate goal of problem elimination through PDCA-based change.

In a Lean culture, the role of leaders is to support daily kaizen. To add energy, to ask questions, to encourage, and to coach without taking over. In this manner, the leader by coaching the team through the improvement process and recognizing that the answers lie with those doing the work, develops the abilities of his people and reinforces the approach to problem solving. The conversations of effective coaching become easier for leaders who understand the work and we have found that daily rounds at the DM Board are the perfect place for leaders to gain that deeper understanding and to support daily improvement efforts of staff.

DM and the Gemba Walk

Gemba is a Japanese word that means the real place where value is created, and the work activities are actually done or products are used. In manufacturing that is known as the shop floor. In the laboratory that may be at anywhere along the production line from specimen collection, transport, accession, processing, testing, and report generation and transmittal. In other areas of healthcare, that place may be closer to the patient at the registration desk, the bedside, the clinic, the operating room, etc. To offer another manufacturing analogy, all along these processes in all aspects of healthcare there are handoffs between “customers” and “suppliers” that can be redesigned and continually improved using Lean principles. The idea of Lean design is that the problems in the Gemba are made visible, and therefore the best improvement ideas will come from going to the Gemba to see.

The DM Board provides visible and strategically meaningful opportunities for leaders to build stronger relationships with managers and team members by engaging them where they work in conversations about their work processes, by coaching for deeper Lean thinking and by praising them for work well done.

Consistently high levels of quality depend not only on defect-free tangibles related to product or service but probably even more importantly on the invisible intangibles involved in local problem solving and decision making. Here is where DM excels as an opportunity for leaders and managers to educate the workforce to see and clarify issues, identify those that need to be addressed by an immediate countermeasure and those that must be resolved and eradicated using systematic, data-driven PDCA problem solving.

Gemba Walks are an opportunity for those leading a Lean enterprise to go and see to observe in order to become better leaders by promoting managerial accountability and employee engagement in the continuous process of improvement in the lean culture. The fine distinction in this walk is that it is not the leader’s job to fix the problem. Walking the Gemba is part of the leader’s participation in the “Check” aspect of Plan‐Do‐Check‐Act (PDCA). On the Gemba walk, the problem review is prompted by the leader with involvement of the manager and the team. In this process the leader can assess how well the teams can see, analyze and clear issues using root cause analysis and testing countermeasures to solve problems based on data. The weaknesses identified in this dialog are the leader’s opportunity to now teach. Leaders should consider the Gemba walk the physical and mental exam to check on the health of the management system and a human development opportunity.

DM serves as the data driven conversation for leaders on their regular Gemba walks to develop people and reinforce Lean thinking and behaviors for continuous improvement with simple questions like “What happened here? What are you doing about it now? What more do you need to know about it? How do you propose to eliminate that root cause?”

According to Liker, “The more clear it is in the workplace what the standards are (reflecting what should be) the more easily the manager can see the gaps and have productive discussions with people in the process. If there is a chart it should be clear if the process is in control (green) or out of control (red). It should be clear where inputs used should be, how much should be there, and when they should be arriving. It should be clear (without flipping through many computer screens) what the technical worker should be working on versus what they are working on. This is called a "visual workplace" and the more it is clear visually what should be happening versus what is happening the more productive the Gemba walks will be.” (5)

Challenges

As with any new behavior, there was an adaptation phase to DM as managers and employees became comfortable with a daily exposure of their work system failures. This required the blame-free Lean culture to be functional in every section so that challenging metrics (failing measures) could be chosen as a visual focus for the work team to direct improvement efforts. Strong managers who engaged their employees and were adept in team-based approaches to improvement adapted to DM as an immediate problem-solving tool quicker than those who preferred the comfort of offering mostly “green day” metrics. These strong managers were more likely to select new metrics throughout the year as former problems were resolved. Most adopted a rule that 3 months of all “green” days signaled problem resolution and stability so that the metric could be retired. Laboratories that performed their work in a serial structure of work stations connected along the path of work flow and could co-locate their DM metric boards could more readily work together in a true customer-supplier fashion, as illustrated for Surgical Pathology, to make improvements that spanned across the value stream and had great impact on the downstream work result.

Let us address the perception that a process of daily rounding may be time intensive. If left to an unstructured process, that may be the case. The approach to DM that we describe provides a structure and process to daily round or huddle at the DM board that is overseen by the manager/supervisor and engages those with delegated authority for daily analysis and presentation of select metrics. Several expectations contribute to brevity. First, a successful metric (a green day) is not discussed, just noted. Second, the meeting is conducted standing up as a rapid visual team review in front of the DM board with a goal of quickly documenting and assessing failures in key processes within the previous 24-hour interval. These DM process requirements maintain a focus on rapid meeting closure. Our experience is that the average DM meeting time expended is 2-10 minutes per day per DM board. Time variation is attributed by unstable and failed processes that may require further sharing of information or questions that arise at the DM board with initial conversations about next steps or subsequent root cause analysis or interventions to be tested. Additionally, senior leaders who incorporate the DM board meetings into their Gemba walks may prolong the regular daily huddle with additional conversations with the staff.

In conclusion, we have found that DM is the key accountability subsystem for managers to continually improve their operations in a structured and visible manner. Strategy and policy can only go so far without quality delivered every day at the level of the work. As Henry Ford said in 1918, “Quality is what counts, and nothing but quality”. (6) We have found DM to be an essential means of delivering on our organization’s quest to achieve ever higher levels of quality.

References

Zarbo RJ, Varney RC, Copeland R et al. Daily Management System of the Henry Ford Production System. QTIPS to Focus Continuous Improvements at the Level of the Work. Am J Clin Pathol 2015;144:122-136. DOI: 10.1309/AJCPLQYMOFWU31C

(2) Liker JK, Convis GL: The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership. Achieving and Sustaining Excellence Through Leadership Development. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

(3) Zarbo RJ. Creating and sustaining a lean culture of continuous process improvement. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;138:321-326

(4) Liker JK, Franz JK. The Toyota Way to Continuous Improvement: Linking Strategy and Operational Excellence to Achieve Superior Performance. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011.

(5) Liker JK. Personal communication, 2011.

(6) Albion MW. The Quotable Henry Ford. Gainesville: University Press of Florida; 2013, pp. 21, 24.