This editorial is reproduced from the American Journal of Clinical Pathology (September 2010; 134:361-365) and outlines a call to arms, a manifesto, as in “a public declaration of principles, policies, or intentions, especially of a political nature." We who are trusted with the higher calling of healthcare must see that the people who are passionate in selflessly dedicating their lives to the well being of others can work in effective and safe systems. After all, "it's not systems that produce quality, its people who do." But systems are designed and lead by leaders and that is where one must start if anything will change from the status quo. Here are my observations and call for leaders to lead change in this most important human endeavor. After all, what will be said of our generation, what did we do with our time here? Maintain the status quo? Not!

Leaders Wanted: A Call to Change the Status Quo in Approaching Health Care, Once Again

Richard J. Zarbo, MD, DMD

(editorial from the American Journal of Clinical Pathology, September 2010)

It has been more than 20 years since Don Berwick, MD, newly appointed administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and well known as the CEO of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, called for a change in American health care to a systems-based culture of continuous quality improvement (CQI). His seminal 1989 article, “Continuous Improvement as an Ideal in Health Care,” highlighted the then “new” (to us) Japanese concept of total quality control or total quality management (TQM) that has been idealized as a model of culture, management, and efficiency since the early 1990s.(1)

The world’s most successful implementation of CQI is the Toyota Production System, now popularly referred to as LEAN or LEAN management. What we know of LEAN are professors’ descriptions during the past 20 years of Toyota’s culture, production system principles, work rules, and process improvement tools.(2-5) The LEAN philosophy at its heart is a culture underlying a core business strategy founded in the ideal of continuous improvement (kaizen) that is based on the knowledge of process variation. It is founded in the management system proposed by W. Edwards Deming, a management guru to the Japanese since the early 1950s, who was discovered late by Western businesses.(6) Looking at the recent decline of American automotive manufacturing, some would say too late.

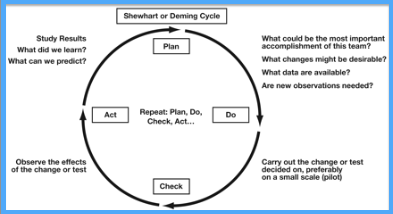

LEAN is a scientifically based approach to quality improvement predicated on the data-driven Plan-Do-Check- Act (PDCA) analytic, also known as the Shewhart or Deming Cycle, that was fairly ineffective 20 years ago in this country when practiced as TQM (Figure 1).

Application of PDCA problem solving seems to be in resurgence, but successful application for change is highly variable, especially in health care. Toyota’s success during the past 50 years, rarely reproduced, derives from a leadership-driven management culture of continuous improvement that over many decades perfected the principles of Deming and innovated aspects of efficient production design with worker empowerment to produce thousands of process improvements, many at the level of the worker, year in and year out.(7) Toyota’s organizational structure and cultural expectations empower organized teams of employees to drive a daily examination of continuous improvement opportunities and learnings, thereby allowing them to be accountable, in charge of their own jobs, and allowed to design their standardized work. The result is CQI bread into the DNA of Toyota’s culture. This cultural transformation of work is what will be required in health care for the true power of LEAN to be leveraged. We failed to change our culture when attempting TQM 20 years ago, and the fate of LEAN will be no different. Transforming the culture of work or, more correctly, the employees’ incentives to relate to each other and work differently is a requirement to obtain success in a LEAN enterprise that is continuously learning and improving. This requires leadership, as only leaders can make this kind of significant change and support realignment of incentives so that workers in connected workstations are encouraged to work collaboratively and horizontally along the path of workflow. This is the only way to obtain the strengths of Toyota’s culture, namely: (1) employees in charge of their own jobs; (2) employees designing standardized work; and (3) employees working to continually improve the work at their own level, with changes made and effectiveness assessed by the customer-focused PDCA cycle.

|

| The never-ending cycle of continuous improvement. The Shewhart or Deming cycle. |

At the core of continuous process improvement is a leader’s understanding of the consistency and reliability of the work product or service produced and the extension of that knowledge to empowered work teams. In other words, the leader’s focus should be on having real-time insight or metrics about in-process variation of work product or service that direct continuous process improvements. As the saying goes, If you can’t measure it, you can’t fix it! This is our challenge in medicine, how to understand what is occurring “in the shop” in real-time, at the level of each piece of work. Ironically, managers of the produce we purchase at the local grocery store are supported by more computerized information to make informed decisions in real time at the level of the individual head of cabbage than we have in most hospitals and laboratories. More often than not, because of paper-based or crude information systems that cannot communicate with each other, this requires manual collection of data, at the level of the worker, where the defects are encountered, to gain a deeper understanding of indicators that are “critical to quality.”

Defects and waste in process are measures of variation. These are the twin enemies of quality. They are also the enemies of productivity and profit, for no one pays for second time rework and we are often not well paid for first-time work. Often not much is known about in-process variation leading to waste and poor quality. In the laboratory environment, we define a defect as a deviation from a predetermined outcome of a process, which is a flaw, an imperfection, or a deficiency in specimen processing requiring delaying or stopping work or returning work to the sender. These defects are noninterpretive defects critical to quality and trigger a series of reworks to satisfy set standards.

Waste can be defined as an amount of time, resources, and human skills that were consumed but did not contribute to value addition in a product or service as it moved across a value-addition process. Waste can take the form of idle time between steps, duplication and rework for each step of a process, and nonutilization of human, organizational, and physical resources. In pursuit of a “zero-defects” performance goal in our quality culture, the Henry Ford Production System, we have designed novel and simple data collection tools to assess current conditions and sources of defects in the workplace to get a handle on these forms of waste and variation.(8,9) This method is applicable to any work environment where automated data are not available or sufficiently granular to lend insight into the detailed root causes of defective work.

In their 1999 Harvard Business Review article, Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System, Spear and Bowen(3) described 4 work rules of LEAN. The first 3 rules deal with the extremely important reduction of variation through standardization of work activities, connections, and pathways. Measurement is the basis of the fourth rule dealing with how improvements are to be made. In this approach to work, problem solving is done by the workers to improve their own work, at the level where the work is done, guided by a teacher, using data, to move incrementally toward an ideal condition through continuous cycles of improvement. This is the scientific approach to problem solving and change based on the Deming Cycle, or PDCA (Plan, Do, Check, Act). Therefore, the fourth rule of LEAN work is founded in measurement that reveals to the manager and worker what is not going right or, in other words, insight into work variation. Notably, the fourth rule also calls for employee engagement, the basis of the team approach to quality improvement.

So, how do the manager and the worker gain insight into the workplace variation that they own and they can change?

For a manager to ensure a system’s consistency and reliability, it is vital to understand the level of variation (defects) in operations on a daily basis in order to focus efforts to bring work quality within predictable limits. This requires continually “feeling the pulse of the machine” so to speak, from assessment of daily metrics. This is the manager’s role in LEAN.

There are essentially 3 types of metrics of value that indicate variation in an operation and that should be used as a basis of PDCA-based “scientifically” designed process improvements. The specific metrics, per se, are best determined by the need for leaders and empowered work teams to understand in real time the quality of work, namely the sources of defects and types of waste associated with the work for which they are accountable.

- Defects that are handed to you by your “supplier”

- In-process defects that you make

- Defects that you hand off to your “customer.”

The definition of the terms customer and supplier used here, although borrowed from manufacturing, are translatable to our own complex processes along the path of workflow in health care. Who passes work to you? (Your supplier.) You rely on your supplier for information, data, parts, tools, tasks, patients, etc. Who requests or gets work from you? (Your customer.) Are customers inside your section, division, or department (internal customers) or outside your sphere (external customers)?

The use of daily metrics in feedback loops to guide quality initiatives that improve processes is illustrated in Figure2. For laboratories, these are the opportunities to understand preanalytic, intra-analytic, and postanalytic variation along the path of workflow.

|

| Customer feedback informing improvements. |

This systematic approach to work improvement is not new. In 1926, Henry Ford,(10) reflecting on the extremely efficient auto manufacturing business he created and that was an inspiration for Toyota, reflected that: “Our system of management is not a system at all; it consists of planning the methods of doing the work as well as the work.” The old way of doing business is to manage outcomes such as labeling defects and misidentifications by detecting defects after the fact. Inspection is a countermeasure when you cannot trust what you just produced, ordered, or received to be defect-free. Inspection itself is rework. It is far better to eliminate the need for inspection on a mass basis by building quality into the product (or service) in the first place. How do we do this? By constantly monitoring in-process feedback and customer feedback to understand variation. It is this “scientific” understanding of the workplace that allows work to be redesigned by educated managers and trained, empowered work teams who use LEAN work rules focused on standard work, workflow principles, and process improvement tools.

Successful change of the status quo is highly dependent on effective leadership and follows from Deming’s call for managers and leaders to adopt the new philosophy of management. That philosophy is nicely summarized by Gabor(11) in The Man Who Discovered Quality: How W. Edwards Deming Brought the Quality Revolution to America.

“In companies that have embraced Deming’s vision, management’s job is to ‘work on the system’ to achieve continual product and process improvement. The Deming-style manager must:

- Ensure a system’s consistency and reliability, by bringing

- Level of variation in its operations within predictable limits, then by

- Identifying opportunities for improvement, by

- Enlisting the participation of every employee, and by

- Giving subordinates the practical benefit of his experience and the help they need to chart improvement strategies.”

By leveraging our investment in the creation of a LEAN managed culture and empowered employees, we have had much success in the large, integrated laboratory operations of the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI. For example, in the surgical pathology division, within 1 year of roughly 100 process improvements, the number of cases with defects was reduced by 55% (including specimen receipt, specimen accessioning, grossing, histology slides, and slide recuts).(12) This number was further reduced by 91% after 2 years of LEAN management in the Henry Ford Production System. Patient safety also wins when there is a focus on waste and defect reduction and work simplification. Through the implementation of process redesign and bar code–specified work processes, laboratory misidentification defects were reduced by approximately 62% overall (95% reduction in slide misidentification defects while increasing technical throughput at the microtome stations by 125%).(13)

And we are never done, and we should never be satisfied with the status quo. In this quality culture, we have become our own benchmark for what is possible. All quality is local. What we do well today we can do better tomorrow. We need only ask: “What would you, as the patient (or customer), expect?” to guide our continuous improvement efforts.

This brings us back to why TQM failed 20 years ago and why LEAN should not fail today. In fact, in personal conversations with Jeffrey Liker, MD, author of The Toyota Way(4) and Toyota Culture,(5) I am informed that 90% of organizations that try to adopt LEAN management fail. Why?

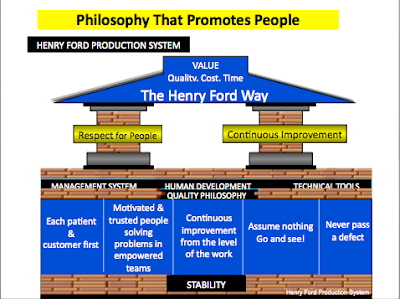

Quite simply, it is very difficult to create and sustain a “Japanese-style” management culture within a “Western” management culture. People with more span of control will have more opportunity for significant change, but that does not mean that you should not try. It does mean that as a leader you must invest your time and efforts differently to change the status quo. As observed in the description of our own quality initiative, “Transforming to a Quality Culture: the Henry Ford Production System”(8): “Toyota’s success is the result of leadership and employee involvement. To be functional leaders, senior staff at Toyota must believe, drive, understand, and live the same training philosophy and employee empowerment that in turn reinforces the culture established by the original company founders.”

It is no stretch to look to the most successful business of manufacturing for health care solutions. Toyota’s culture that foremost values respect for people equally with continuous improvement most closely melds with the culture of health care that is invested heavily in well-trained but often uncoordinated care teams. According to Liker and Hoseus(5) in Toyota Culture: The Heart and Soul of the Toyota Way, “LEAN systems and structure is buried 2 levels down in Toyota’s model and not the focus.” Without the creation by leadership of an organizational structure and value system to encourage and support a bottom-up, worker-empowered culture of continual improvement, significant and sustained change à la the Toyota Production System with hundreds of process improvements is not possible; only sporadic leader directed projects, often prompted by crisis, and application of disconnected quality tools or focused but limited kaizen events will be seen.

From my personal learnings during 5 years in promoting a LEAN culture in the laboratories of the Henry Ford Health System, this is how I see the required steps for leaders to transform to an effective PDCA-based culture of continuous process improvement in an existing non-LEAN culture, with my apologies to Deming and his 14 principles of management. Upper leadership and midlevel management must agree on and drive the following elements:

- There must be one culture, one incentivized way of doing things. If there are too many models, silos are perpetuated and workers doubt sincerity of the change. Confusion results, and workers, unsure of what is expected, continually seek clarity about the direction. This lack of cultural coherence results in the conclusion that they are being subjected to another management fad of the month that can be dodged or outlasted. This is leadership failure. Welcome to Liker’s 90% of places that tried LEAN and failed!

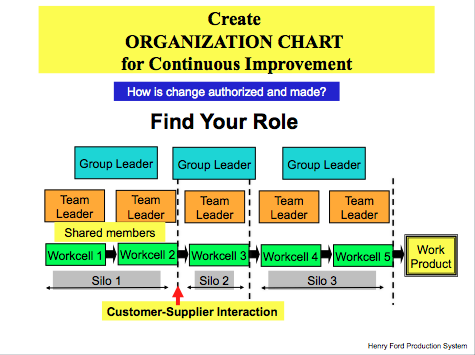

- Leaders and managers must adopt the basic principles of management that allow the process- improvement model to work effectively across work units and business units in a horizontal manner as the work flows. A spirit of selfless collaboration enables the breakdown of the silos to achieve true horizontal management. Again, incentives must be realigned for the new behavior to become reality, and this must come from top management.

- Leaders must adopt their new role to continually work on the “system of work,” push the change with their “direct reports” and workers, and, by doing this, live by the new culture. Absent elements 1, 2, and 3, the remaining points are not sustainable. Stop now. You’re into lip service.

- Structure must be established to teach and adopt standard work rules that promote standardization of activities, connections, and pathways and allow empowered workers to implement PDCA-based process improvements with their established teams.

- Structure must be established to teach and adopt process improvement tools aimed at the chief enemies of quality, namely, variation, defects, and waste. Eventually, sufficient efficiencies will be achieved in workflow smoothing, work simplification, and just-in-time approaches to work, resulting in increased productivity, throughput, timeliness, and customer satisfaction with decreased rework and cost.

- Organizational structures must be created to sustain the preceding and recognize the value of engaged workers, their effective, collaborative teams, and their leaders.

LEAN success does not result from merely training in the process-improvement tools; it is founded in culture and the empowered worker! We need more than a handful of foot soldiers trained in “boot camps.” Success will require effective battalions and brigades supported by impassioned generals. Success starts and ends with leadership. The current challenge for businesses of any type, and especially health care, is how to adopt the Deming style of management rather than merely how to apply the principles and use the tools of Toyota’s efficient production system. I have related my approach above.

The key lesson from the TQM history in health care is that what is really required for success is a change in culture, that is, the behavioral incentives that derive from the norms, values, belief systems, decision-making processes, and political power bases that make an organization function. Anything less comes up short when the goal is to effect continuous process improvement. Are you ready to lead?

From the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI.

- Berwick DM. Continuous improvement as an ideal in health care. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:53-56.

- Womack JP, Jones DT, Roos D. The Machine That Changed the World: The Story of Lean Production: How Japan’s Secret Weapon in the Global Auto Wars Will Revolutionize Western Industry. New York, NY: Rawson Associates; 1990.

- Spear SJ, Bowen HK. Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System. Harvard Bus Rev. September 1, 1999:96-106.

- Liker JK. The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles From the World’s Greatest Manufacturer.New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2004.

- Liker JK, Hoseus M. Toyota Culture. The Heart and Soul of the Toyota Way. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2008.

- Deming WE. Out of the Crisis. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 1986.

- Ohno T. Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production. Portland, OR: Productivity Press; 1988.

- Zarbo RJ, D’Angelo R. Transforming to a quality culture: the Henry Ford Production System. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;126(suppl 1):S21-S29.

- D’Angelo R, Zarbo RJ. The Henry Ford Production System: measures of process defects and waste in surgical pathology as a basis for quality improvement initiatives. Am J Clin Pathol 2007;128:423-429.

- Ford H. Today and Tomorrow. New York, NY: Doubleday; 1926.

- Gabor A. The Man Who Discovered Quality: How W. Edwards Deming Brought the Quality Revolution to America: The Stories of FORD, XEROX, and GM. New York, NY: Times Books; 1990.

- Zarbo RJ, D’Angelo R. The Henry Ford Production System: effective reduction of process defects and waste in surgical pathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:1015-1022.

- Zarbo RJ, Tuthill JM, D’Angelo R, et al. The Henry Ford Production System: reduction of surgical pathology in-process misidentification defects by bar code–specified work process standardization. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:468-477.